Using examples, critically discuss the contention that paleoclimate research is essential in understanding the impacts of current and future climate change.

Introduction

Our understanding of the impacts of current and future climate change has increased significantly over the past decades but it is still unknown (Knutti, 2019). This essay will argue how paleoclimate research is essential in our understanding of current and future climate change, while also discussing the contention around this topic. Paleoclimate research studies climate proxies to reconstruct past climate globally (Climate Research and Development Program, 2021). This research helps scientists assess the possible impacts of anthropogenic climate effects (Hansen and Sato, 2012) and means we can learn more about the impacts of large-scale climate changes (Schmittner, 2018).

This essay will critically discuss 3 time periods: the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), the middle Miocene climate optimum (MMCO) and the eemian (the last interglacial), which show the importance of paleoclimate research in helping to aid the understanding of climate change. It will then touch on the 8.2ka event before providing an overall summary on the importance of paleoclimate research and discussing how uncertainty plays a big role in the significance of paleoclimate research. Finally, it will come to a rounded and clear conclusion which will bring together all points made throughout the essay.

PETM

The PETM occurred 55.6 million years ago - being the closest geologic analogue for anthropogenic carbon release (Haynes and Hönisch, 2020), it is therefore essential for our understanding. In the PETM, carbon - which was isotopically depleted, was released into the atmosphere system with the subsequent impacts; prolonged warming, ocean acidification and changes to ocean circulation occurring (Haynes and Hönisch, 2013). These impacts are somewhat like present day conditions, with Godbold and Calosi (2013) stating that currently there has been an approximately 0.2°C of warming per decade and a rapid increase of CO2 in the oceans, resulting in reductions in pH (ocean acidification). This shows, by using research on the PETM, we can help to broaden our understanding of why the current climate is the way it is, and how it may look in the future.

However, when comparing the rates of carbon addition during the PETM and the modern era, it was found that rates were on average 10 times slower (Foster et al., 2018). As the periods differ so much, it makes it harder to use past analogues to understand future climate. But when comparing the rate of the last 150 years it was found that the rates were much more comparable. This suggests that the PETM is potentially a closer analogue for present and future climate change than was first thought (Foster et al., 2018).

A major cause for contention is that, although the PETM has been studied significantly, there has been vastly varying estimates for atmospheric CO2 concentrations (Meissner et al., 2014). Pearson and Palmer (2003) state they found concentrations in excess of 2000 ppm in the pre PETM, whereas Hilting, Kump and Bralower (2008) estimated concentrations at less than 300 ppm. The huge variety in previous studies about past CO2 concentrations, makes it very hard to model and understand current and future climate impacts. However, Meissner et al (2014) conducted a study using a novel model-data combination, where they found that simulated sea surface temperatures correspond most with atmospheric CO2 concentrations of between 840 and 1680 ppm. Furthermore, 1680 ppm is the best fit between model and data for sediment cover. This is significant in narrowing down previous conditions, in order to help our understanding of current and future climate impacts (Meissner et al., 2014).

MMCO

The MMCO occurred 17-15 million years ago and it was a warm period, breaking a long-term period of cooling, declining CO2 levels and ice sheet growth in the Antarctic (Methner et al., 2020). There is increasing evidence of elevated CO2 levels in the MMCO, with some estimates characterising the CO2 variability between 300 and 500 ppm (Greenop et al., 2014). Most proxy records indicate this range is close or slightly higher than the current values (Steinthorsdottir et al., 2020). Using this evidence, it’s clear that the MMCO has similarities in the scale of global change when compared to the current rise in atmospheric CO2, as well as rising global temperatures and decreasing ice volume (Methner et al., 2020). The range of CO2 levels and temperature in the MMCO can be used to help to understand future impacts from climate change. The warming levels of 3°C-7°C coincide with the IPCC’S scenarios like RCP 4.5 and RCP 6.0 (Steinthorsdottir et al., 2020).

There is evidence to show that the high CO2 levels and the main eruptive phase of the Columbia river flood basalts are linked because the dates in which both occur coincide. This helps to support the view that the warmth in the MMCO period was, at least somewhat, driven by an increase in volcanic emissions (Foster, Lear and Rae, 2012). This is essential in our understanding for future climate impacts, because according to Aubry et al (2022), with continued global warming there is expected to be an increase in extreme rainfall, which has been linked to induce volcanic activity by several case studies. Therefore, by using Foster, Lear and Rae, in the future we would expect to see warmer global temperatures. However according to Kasbohm and Schoene (2018) there is not enough high precision geochronologic data to make a confident link between the two events.

Eemian

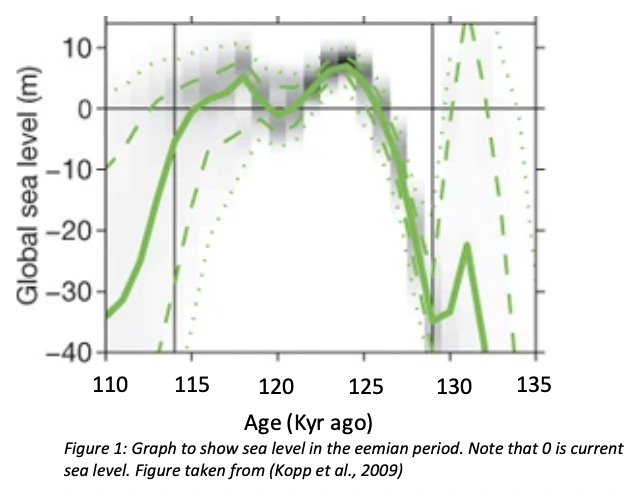

The eemian, which is the last interglacial, occurred between 129,000 and 116,000 years ago. Its characteristics, such as global average temperatures being 0-2°C above current levels and the sea level 6-9m above the present level (Salonen et al., 2018) - make it essential in our understanding of future impacts. Looking at figure 1, we can see that the sea level in the eemian acts as a useful analogue for the future. The graph shows the middle peak height of 7.2m and according to Kopp et al (2009) there is a 95% probability of sea level having exceeded 6.6m at some time during the eemian. This shows the significance of research done about the eemian, as it shows potential consequences to our planet if global warming continues at its current and projected rates.

It is suggested that 2-3.5 meters of the 6-9m came from the Greenland ice sheet (GIS), showing how fundamental the GIS is in global sea levels now (Bradley, 2012). Furthermore, the current sea level is rising, and the projections are that by 2100 it will have risen by 1-1.25 m, with the assumption the west Antarctic ice sheet doesn’t have a major collapse (Bradley, 2012). Although studying the sea level in the eemian is useful for our understanding, current sea level rise is still hugely difficult to predict. This is mainly due to ice sheets being very difficult to simulate and the lack of a “good paleoclimate analogue for rapidly increasing anthropogenic climate forcing” (Hansen and Sato, 2012).

In a paper by McGowan et al (2020), they study the eemian climate of southeast Australia and particularly droughts. First, they found increased Mg concentrations which is a sign of drier conditions, as well as records of southeast Australia experiencing multiple centuries of decreased precipitation, variability in temperature and an increase in atmospheric dust. Furthermore, it has shown that in a similar climate to the eemian (today or near future climate) there is a risk of mega-droughts, and with anthropogenic global warming evermore present, the severity of these events is likely to increase (McGowan et al., 2020).

The eemian however, is regarded as an imperfect analogue for anthropogenic global warming because the climate forcing was different (Salonen et al., 2018). The last interglacial warming was due to orbital forcing and not greenhouse gas loading which is occurring now (McGowan et al., 2020).Furthermore, Salonen et al (2018) goes onto say climate syntheses are being hindered by fragmented data, especially in the high latitudes of the northern hemisphere. These high latitudes are essential for climate records, modelling current and future climate changes, as well as showing past warm climate stages (Salonen et al., 2018). This massively takes away from the importance of paleoclimate research for our understanding, because if we are lacking all the facts then we would be unable to show the full picture of climate change in the future, which may subsequently affect future policy and law decisions.

8.2ka event

The 8.2ka event occurred approximately 8200 years ago, and it is known to be the largest sudden climatic change of the Holocene period (Griffiths and Robinson, 2018). However, there is a lot of confusion and debate in literature about what it is and how long it lasted (Thomas et al., 2007). It can act as a reference point for future climate trends firstly, because of the Greenland ice sheet melting and secondly, by using RCP 8.5- the projected input of freshwater into the north Atlantic is of the same magnitude as simulations done about the 8.2ka event (Aguiar et al., 2021).

General Paleoclimate

Paleoclimate research has significant key benefits which make it essential in our understanding for current and future climate change impacts. By studying millions of years worth of paleoclimate data, we can understand past periods of rapid climate change which can enable us to predict and model our future climate (Snyder, 2010). The significance of paleoclimate research is shown through the use of it in the IPCC’s 4th assessment report, where they use the research to help understand: responses of ecosystems and humans to previous climate variability, causes of climate variability and the frequency and the extent of extreme events (Thompson, 2011). Lastly, the paleoclimate record is the fundamental core for our understanding of the potential range and rate of climate change, whilst continuing to reveal insights into the earths response to rising CO2 concentrations (Tierney et al., 2020).

Contention

Whilst paleoclimate research has a huge number of positives which make it essential to our understanding there is contention about its uncertainty. Firstly, there is uncertainty within the climate proxy. For example, the calibration process of a proxy assumes the relationship found today will contain all the different climatic conditions of the past. However, due to evolution as well as other environmental changes a different relationship could be produced (Snyder, 2010). There is also the issue with timescales when it comes to paleoclimate research. Timescales are essential in understanding correlation of climate changes over time. Alley et al (2003) compared Greenland and Antarctica ice cores and found that over long timescales there is a significant positive correlation between the two. But when they move to a smaller timescale, they find the result is the opposite- a significant negative correlation.

Lastly, there is a distinct lack of knowledge and understanding about the mechanisms of abrupt climate change as well as the key climate thresholds (IPCC,2007). These are crucial as they could cause a significant acceleration in sea level rise of in regional climate change. The way that ice sheets grew and disintegrated are still not know well enough to truly understand and use confidently in our predictions for future climate change (Jansen et al., 2007).

Conclusion

This essay concludes that paleoclimate research is essential in understanding the impacts of current and future climate change. The three key time periods this essay has focused on demonstrate how the research can be used and modelled to predict and understand what our future climate will be like along with the projected impacts. This essay accepts that the research has its flaws with uncertainty being the most significant one, but as a benchmark for climate models (which help to predict our future) the research doesn’t have to be perfect, as it still contributes so much to our understanding of current and future climate change impacts (Tierney et al., 2020).