How can the reduction of light pollution help to maintain and improve integral ecological processes in an urban area?

Introduction

The pollution of light into the atmosphere has been increasing sharply over the past 12 years, with a shockingly high average increase in artificial light of 10% per year (Falchi and Bará, 2023). Because of this, there has been multiple problems for several species, such as an increase in danger for prey, as predators take advantage of better light levels or rapidly diminishing melatonin levels (Falchi and Bará, 2023); recognising light pollution as a serious biodiversity threat (Stone et al., 2015). The light pollution, which is becoming more prevalent in modern day society but is still lacking hugely in understanding, is that of pollution in the form of artificial light at night (ALAN) (Khan et al., 2020). ALAN can be closely linked with population density and economic activity (Schligler et al., 2021), and with over 60% of the population globally expected to live in cities by 2050 (McLay et al., 2019) we can expect the volume of ALAN to increase. With over 80% of the world population living under light polluted skies (Grubisic et al., 2019), combined with the growing urban population, it would be no surprise to see this number reach 100% sooner rather than later.

Urban planning methods such as, the equal distribution of luminaires in order to reduce over lighting or increasing one’s knowledge of the impacts on animals and insects from a skyglow are two key methods which can help in the battle against light pollution (Pothukuchi, 2021). This essay will first start with a section on defining light pollution thoroughly, engaging in the different types and giving the history behind it. It will then look at the effect’s pollution has on species, before looking at methods to mitigate against pollution. Techniques such as “Project Tatort” will be looked at and analysed to see how it can potentially be used in urban planning. Case studies of multiple different cities will be used in the ‘mitigating light pollution via urban planning’ section. Lastly, it will come to a clear and rounded conclusion, bringing together all the points made throughout this essay.

What is light pollution?

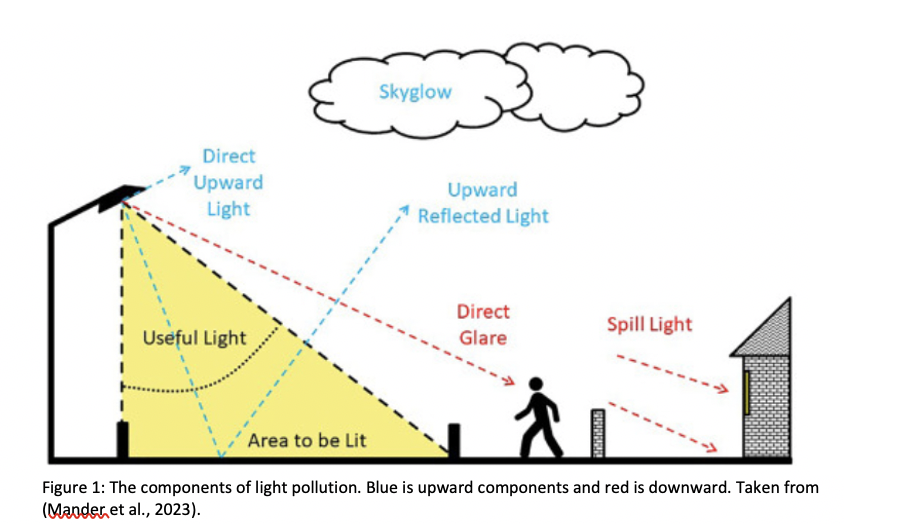

Light pollution comes from artificial lights used to light streets and homes, emitting light to the lower atmosphere which will then stay there due to aerosol particle concentration (Rodrigo-Comino et al., 2021). It’s been found by most light pollution researchers an average of 15% reflectivity is representative of illuminated surfaces like concrete (Green et al., 2022). Figure 1 below, shows a clear breakdown of what light pollution is, where the upward reflected light, combined with the direct upward light causes skyglow (Mander et al., 2023). Even though at times skyglow can be so faint that humans can’t see it, it has the potential to threaten 30% of vertebrates and 60% of invertebrates that are nocturnal or sensitive to light (Irwin, 2018).

Currently, there is a transition occurring in street lighting, moving from low-pressure sodium (LPS) and high-pressure sodium (HPS) to light emitting diodes (LED) (Rowse, Harris and Jones, 2016). LED’s can be broken down into three main categories; cool neutral and warm, with ‘cool’ having the highest colour temperature and warm the lowest. LED technologies are contributing to higher levels of night-time illumination, which for people residing in underdeveloped and rural areas is a positive impact but it is raising concern for light pollution affecting species (Pothukuchi, 2021). The effect of wavelength on a species is also important, insects are traditionally attracted to shorter wavelengths due to the sensitivities in their eyes, so you would expect to find lots of them around old technology gas lights (Rowse, Harris and Jones, 2016).

Effects on ecological processes

There are multiple crucial processes for animals and, particularly insects to survive. This section will investigate how light pollution affects each process. The main processes which will be focused on are behaviour, phenology and lastly mortality, which is not a process, but is still hugely insightful to efforts into gaining knowledge and understanding about the effects from light pollution.

Behaviour

Due to ALAN, it’s been found that the ‘animal instinct’ is reduced, with the example of dog whelks being used. Dog whelks living under light pollution were found to be less likely to seek refuge from a predator when living under light pollution (Hoffmann, Schirmer and Eccard, 2019). However, except from predator-prey dynamics, the studies on effects of ALAN are limited (Hoffmann, Schirmer and Eccard, 2019). In insects, the biggest effect from ALAN is phototaxis, the phenomenon to do with the attraction to light source proximity. Positive phototaxy (going toward the source of light) can cause insects death, burns, entrapment in the light or exhaustion (Katabaro et al., 2022). Shier, Bird and Wang (2020) did a study in California looking at the impact of ALAN on Stephens’ kangaroo rat (SKR) foraging behaviour. It was shown that SKR used fewer resource patches under ALAN in comparison with control patches and this can be down to several reasons. Firstly, they may just be blinded by the artificial light and secondly, they forage less when they are more visible which they would be under ALAN (Shier, Bird and Wang, 2020). The nonvisual form of communication which SKR use means that they are more impacted in their foraging then those species who use visual communication. Whilst low intensity lighting and ‘warm’ LEDs have previously been shown to be less disruptive to wildlife than higher intensity lighting and HPS, the results from this study find that even low intensity, warm LEDs, will have huge negative effects on SKR foraging decisions (Shier, Bird and Wang, 2020).

Mortality

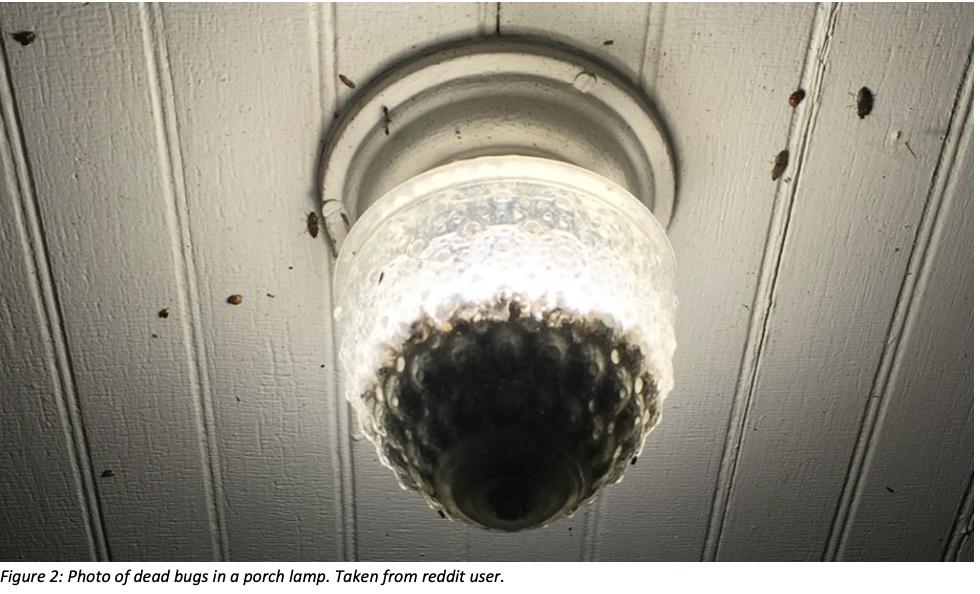

Perhaps the most important impact of ALAN on species is mortality. In a study done by Tel Aviv University’s School of Zoology on the impact of ALAN on rodents, they found that the colonies died within days, on two separate occasions. The average life expectancy of mice is 4-5 years and with the autopsies revealing no abnormal findings it was assumed that the exposure to ALAN had caused some impairment to the immune system and then a pathogen wiped them out (Tel Aviv University, 2023). Unlike rodents, insects are more directly affected by light pollution, in the form of streetlights. Approximately 30-40% of insects which approach streetlamps die very soon after due to overheating, collision, dehydration or predation (Owens and Lewis, 2018). This can be seen in figure two below, a picture shared by a reddit user, and you can see the massive amounts of bugs inside and around which have most likely died via overheating or dehydration.

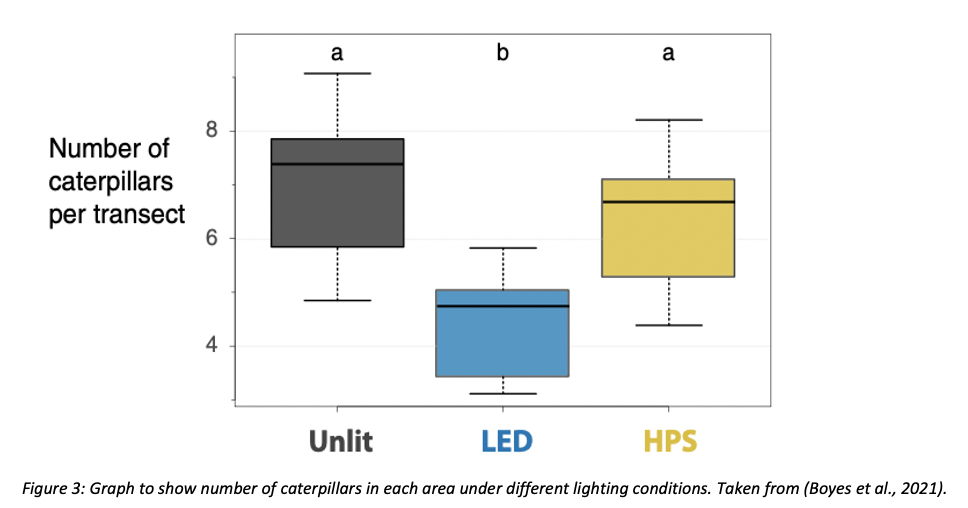

In a study done looking at the impact of ALAN on moth caterpillar numbers it was found that in the presence of street lighting there was a reduction of nearly one half in caterpillars in hedgerows and a reduction by 1/3rd in grass margins (Boyes et al., 2021). Interestingly, as shown by figure 3, the HPS and unlit transects are actually very similar, whereas LED is significantly lower. Feeding behaviour of caterpillars being disrupted by LED lighting and not HPS lighting can be concluded from this study.

Phenology

Phenological shifts because of the effect from ALAN have been reported in multiple species such as plants, insects and birds (Dominoni et al., 2020). Light pollution affects the ability of animals use of natural light cues to synchronize their circadian rhythm and to time important life events like growth and reproduction. This has been put down to the cues being shadowed by ALAN, which has an increasing potential to disrupt the processes in the environment (Hoffmann, Schirmer and Eccard, 2019).

Reproduction

Reproduction from species is a crucial process which can affect population dynamics in an area, and the altering of cycles may lead to significant consequences. A good example of a species being affected by ALAN is the case of the glow-worm. They use bioluminescent signals like glows or flashes of light to attract mates, meaning when ALAN is present, it influences a glow-worm’s ability to detect the signals (Elgert et al., 2020). The consequence from this is mating success rates may decrease meaning number of offspring decrease, altering the population dynamics of an area (Elgert et al., 2020). The impact on glow-worms is dependent on the wavelength of light, where wavelengths less than 533nm increase brightness of light but decrease flashes in Aquatica ficta and in Photinus obscurellus, amber light had the biggest impact (Grubisic and van Grunsven, 2021). Lastly, in a study on toads, it was found that male fertilization success rate was negatively impacted by ALAN, with the rate being 25% lower under lux 5 than those at the control (Touzot et al., 2020). The physiological mechanisms causing this are relatively unknown however may be linked to spermatogenesis; the production of sperm (Touzot et al., 2020).

Dominoni, Quetting and Partecke (2013) found that even very low levels of light intensities can affect reproductive timings; not only in the egg-laying phase but before that, advancing gonadal growth and testosterone production by up to one month. This is a potential positive impact on the birds, with enhanced mating opportunities due to the earlier egg laying (Thawley and Kolbe, 2020). A potential trade-off between early onset/ egg production frequency increases and lower quality eggs was hypothesised however rejected due to only weak evidence being found (Thawley and Kolbe, 2020). Furthermore, Wang, Tuanmu and Hung (2021) found another positive effect due to ALAN whilst looking at barn swallows. They suggested the positive effect is from an increase in foraging ability at night, finding that nestlings under higher ALAN intensity were fed more often and had a higher fledging success than those under low ALAN intensity (Wang, Tuanmu and Hung, 2021).

Sleep

ALAN was found to have caused birds to wake up earlier and leave the nest-box earlier, resulting in less sleep. There was an overall reduction of sleep of ¾ of an hour, mainly occurring as a result of waking up earlier and not sleeping later (Raap, Pinxten and Eens, 2015). The effect of a lack of sleep for birds has been proven to have multiple negative effects. Some of these include the lack of consolidation of memory for songbird learning as well as the missed opportunity to recover from daily stress (Vorster and Born, 2015).

Mitigating light pollution via urban planning

Urban planning “takes into account the potential and limitation of the natural and human entities in question”, including the causes and impacts of the dynamics that affect the city (Bolay, 2019). Night-time light pollution is exacerbated by poor design, installation and maintenance of streetlights (Gaston et al., 2012). As shown in figure 1, the street lighting is meant to light the road surface and objects below the light, however, light is often emitted upwards or horizontally due to poor design. One way that urban planners can overcome this flaw is to change the design of the streetlights.

Project “Tatort Streetlight”

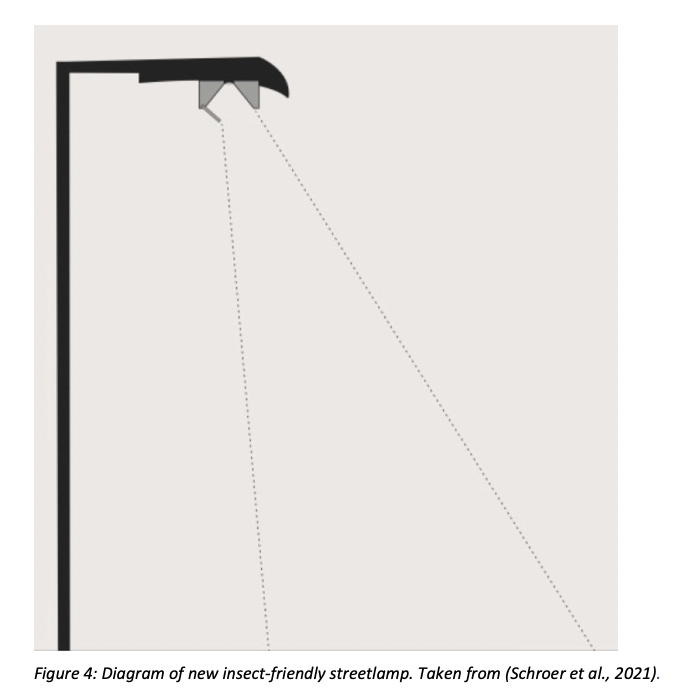

Project “Tatort Streetlight” is a project which looks at 4 German cities and aims to use insect friendly lighting design (see figure 4), as well as promote mutual exchange of topics and obstacles and highlights issues, and provide a clear connection pathway between research and applied knowledge (Schroer et al., 2021). The insect friendly streetlight will direct light only where it is needed with a wide angle at the targeted area and shielded light source using shutters. The aim is that it won’t be visible from water bodies, floodplains or other habitats. With moths being attracted to HPS from over 20m away as well as cassis flies and mayflies being attracted from 40m, this project will aim to reduce attraction and the barrier effect by improving light distribution geometry (Schroer et al., 2021).

Whilst it is too early to know how much of a difference these will make; this project is a first of its kind; trying to communicate between stakeholders with ecological lighting planning at the forefront of discussion. This new method of design is fundamental in future urban planning, with the involvement of all relevant stakeholders necessary and of great importance so that all aspects of both benefits and adverse effects can be discussed.

Legal lighting limits

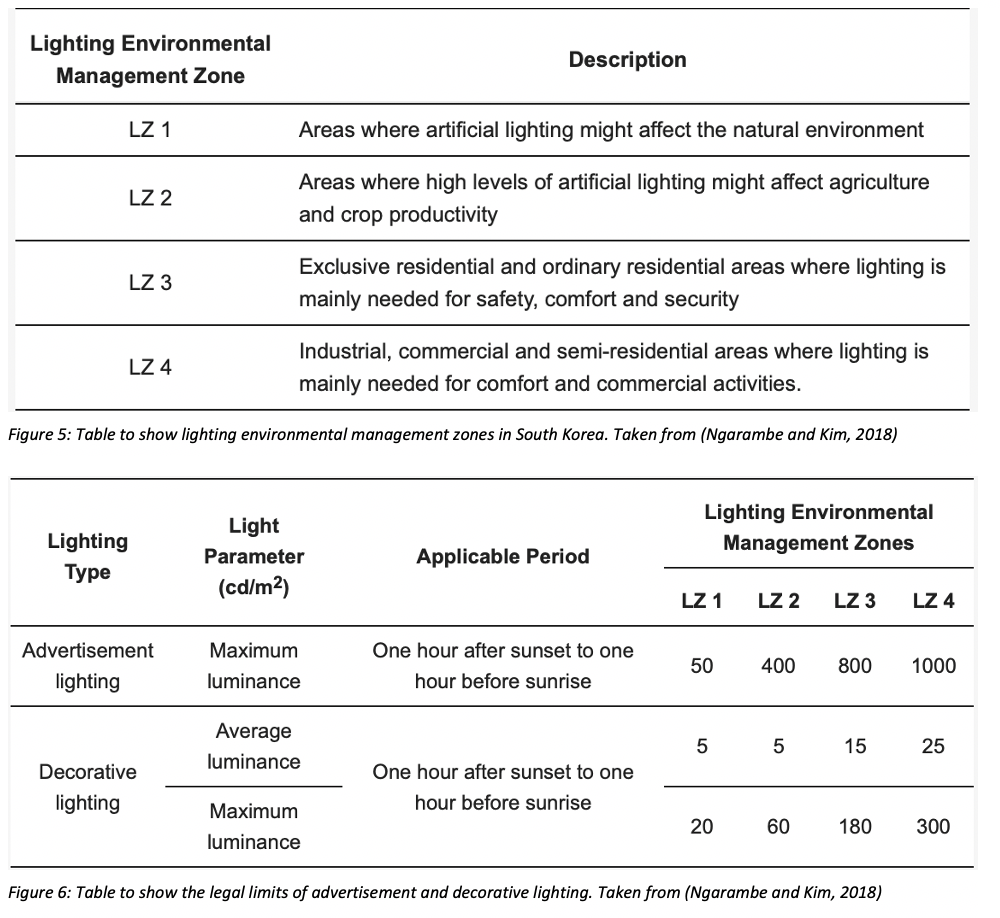

Whilst street lighting is considered the biggest threat to insects, the presence of advertisement and decorative lighting shouldn’t go under the radar. In Seoul, South Korea, they have lighting environmental managements zones with limits for each zone, as shown in figures 5 and 6 below. In their study, Ngarambe and Kim (2018) found that in residential areas nearly 40% of advertisement exceeded the legal limit, and in semi-residential, industrial and commercials areas, 28%,39% and 30% exceeded the limit. For decorative lighting in the 4 zones they all exceed the legal limit also. This study can be supported by one done by Zielinska-Dabkowska and Xavia (2019) in Bahnhofstrasse, Switzerland who found a luminance value of 2151 cd/m3, 86 times the limit for that region. Whilst this may seem like legal limits on lighting is a bad idea, these studies highlight the importance for further and better regulation on the matter. Street and security lighting designers are advised by professionals on situations such as the Illuminating Engineering Society, that they should use full cut-off or semi cut-off luminaries in order to minimize the dispersal of lighting (Ngarambe and Kim, 2018). No such advice exists for advertisements

Ngarambe and Kim (2018) recommend that South Korea should consider a curfew time for business to shut off advertisement and decorative lighting completely as is the case in France.

Reducing light volumes

Whilst we are still yet to completely understand how insect taxa respond to artificial light of varying spectral composition (wavelength), it is known that reducing light usage full stop would help ecological processes (Owens et al., 2020). Monochromatic LEDs can be designed in a way to produce any desired wavelength (colour), so when it is found what specific wavelength is best for insects, in theory, we can then design lights with the least effect on insects (Owens et al., 2020). It has been found that long wavelength (warmer and amber tones) causes little flight-to-light behaviour in insects, as well as having the least suppressive effect on melatonin which overall may reduce the impacts on insect physiology and development (Owens et al., 2020).

Mitigation of light pollution is a potential solution, and it links in with the “Project Tatort” section, where proper shielding must be installed in order to reduce the atmospheric glow. This study, however, says to focus less on proper shielding and more on dimming the light sources to the lowest acceptable level, and importantly on reducing the number of streetlights in and around vulnerable ecological areas (Owens et al., 2020). Ecotourist hotspots, such as parks, could potentially have shielding at the top and the bottom to reduce the potential impact on nearby biodiversity.

Governments have tools that they can put into policy and implement. Increasing the extent of unlit natural and seminatural areas (Schirmer et al., 2019) and a “Project Tatort” strategy of reducing the “trespass” of lighting into unneeded areas, along with a controlled orientation are perhaps the most important tools (Lacoeuilhe et al., 2014). Urban planners should consider, not just the physical network of corridors and patches to defining urban greenspace but also the nocturnal network; formed by dark areas (Schirmer et al., 2019). Doing so will support urban wildlife best.

Conclusion

This essay concludes that it is fundamental that urban planning efforts on the topic of light pollution increase and, in the future, tools should be implemented. With lighting becoming more energy efficient through new technology such as LEDs, it also becomes more cost-effective. This is good for the customer and bad for the animals and insects. As light becomes more cheaper, consumption naturally increases, therefore light pollution also does. With the growing concern in safety at night for people, women especially, there are more and more calls for more street lighting. This creates a natural trade-off for policymakers and planners, between, essentially human safety and biodiversity. Therefore, techniques such as “Project Tatort” and better professional advice for advertisement lighting pollution should be used. Better recognition for the nocturnal network would have huge benefits for ecological processes. The acknowledgement of these darker areas combined with the network of natural patches and corridors is necessary for the protection against light pollution, but also in the increase of environmental awareness. Environmental awareness is fundamental for an urban planner, and it should be near the forefront in their decision making. Understanding that LEDs don’t just magically make everything better for everyone just because they are very energy efficient or the knowledge that skyglow has a huge effect on female reproduction is essential when trying to combat light pollution.